To begin with, here is a fact: No blues—no rock and roll. The entire evolution and development of the art form grew directly out of the blues and blues influences. There was certainly later development and other influences that worked their way in, but everything about rock and roll was built completely and directly upon the blues.

These days, country also leans heavily in this direction with borrowed riffs, rhythms and grooves, and other key harmonic aspects that came directly from blues roots. Even the use of some instrumental applications like slides on guitar, or harmonicas played using modes, note bends, etc. all have specific historic origins in the blues world. This was not how these European instruments were played before they were adapted by early blues artists. Everything was changed and shaped in the blues world before becoming mainstream later.

Another misconception possibly, is the definition of what blues is—and isn’t. Blues isn’t just “12 bars, and a pentatonic scale,” although these things are a part of the art from that also have direct connection in other American musical art forms mentioned above. There is more to the puzzle though:

By specific definition, blues has a unique harmonic structure that differs from most standard western music. It is a modal music, based on inherently dissonant intervals. These things are familiar to us now, as they have become so ingrained in our collective culture. However, they were something new and foreign not that many decades ago. To go a bit into the weeds here with this, here are a couple of tidbits: The blues is largely built around a dominant 7th interval (major 3rd or minor 3rd in a major or minor scale, played together with the b7 sound). This interval has inherent dissonance, tension and pull for resolution. This interval existed in western music, but had very specific application. It is, however, primary and a foundational harmonic structure in most blues music and blues progressions. As a result of this, there are other harmonies and scales that blues brings to the musical table, that would never have been common in either European classical or folk music. I will do future videos on posts just on this key aspect of the music that also became THE key aspect of rock and roll in slightly different ways.

Keeping all of this in mind, here are key things you can learn, by immersing yourself in the blues world:

- The Language and Vocabulary: a range of standard blues riffs, themes, structural aspects, rhythms and grooves, that show up repeatedly in rock, country and other genres. Rock music, especially earlier forms and what we call “Classic Rock” now, was almost completely structured around pentatonic scale based riffs, runs and progressions. Additionally, when I was subbing in country bands a lot during an aspect of my music career, my reference notes on songs constantly listed specific blues song riffs, “heads” and themes, structures, or related things to help me remember specific country songs—especially songs by more modern artists.

Having all of these things in my back pocket as a player, made learning songs, especially songs in classic rock or more modern country much easier than it otherwise would be. There are other key things though that, immersion in blues, learning blues songs, and listening to classic blues artists helped me do…

2. Playing More Creatively and Efficiently over Chord Changes: One thing that is important to know, and something that will become more obvious as you go below the surface in the blues world, is that the best players in this art form, choose notes carefully and change how they play, even within a standard pentatonic scale, depending on what chords they are playing over in a progression. Understanding this made me a better soloist and rhythm player regardless of the genre. Here is the key and something to help you understand how this works:

The standard minor and major pentatonic scales that most everyone who picks up a guitar learns early on, are really “common” and “passing” tones across chord progressions that have lesser or greater tension and connection, depending on which chord in the progression is being played. For background, unlike standard western musical, and even many jazz, progressions, the interval of the 3rd note in each chord, with an added sound of the b7 (something common in blues), is very common, and is often in most every chord in a blues progression (unlike most standard western music). Also, in blues, it is common for minor sound to be played over chords that have major 3rds. If you listen to skilled blues players, they will change notes, or note approaches, that they use in solos over some chords to lessen this inherent major/minor tension. As an example of what often happens, as a player plays notes over the I chord (the tonic chord in a specific key), they will avoid the minor 3rd in the scale if playing a minor pentatonic, OR even bend that note up so it is closer to the major 3rd. However, when the progression changes to the IV chord, now this sound is in the chord as the b7 note. This certainly may have been an intuitive rather than intentional thing with many early blues players, but it is obvious if you listen closely that often this made all the difference in the sound and approach.

Understanding how all of this fits together in what is typically a fairly simple musical structure, helps you as you move into other types of harmonic structures and chord progressions that may be more complicated. For example, in jazz finding those common and passing tones for solos is a critical skill. This is also true in many modern country and rock genres where it is vital that a player find modes or scales, that work over specific progressions, key changes, etc.

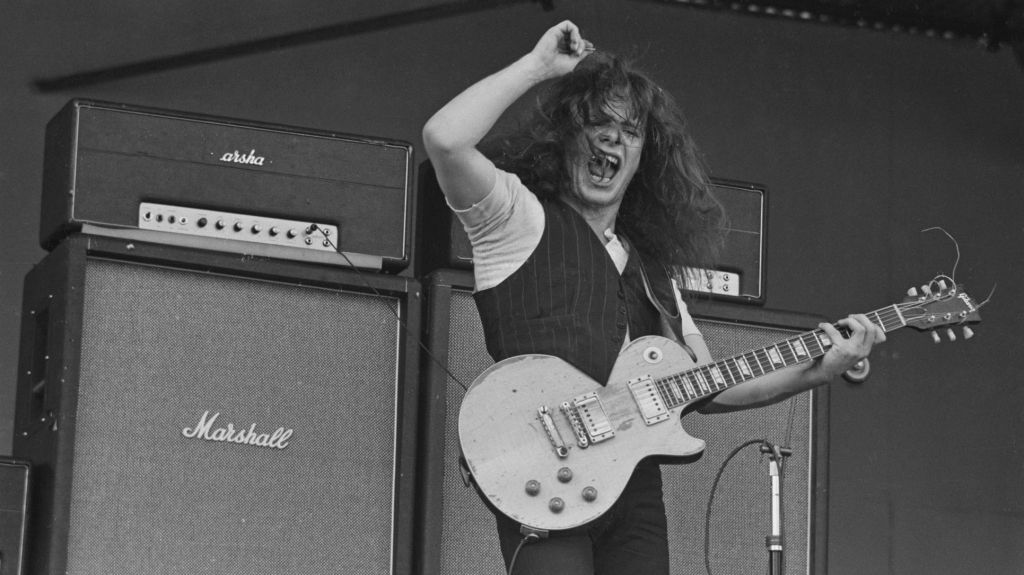

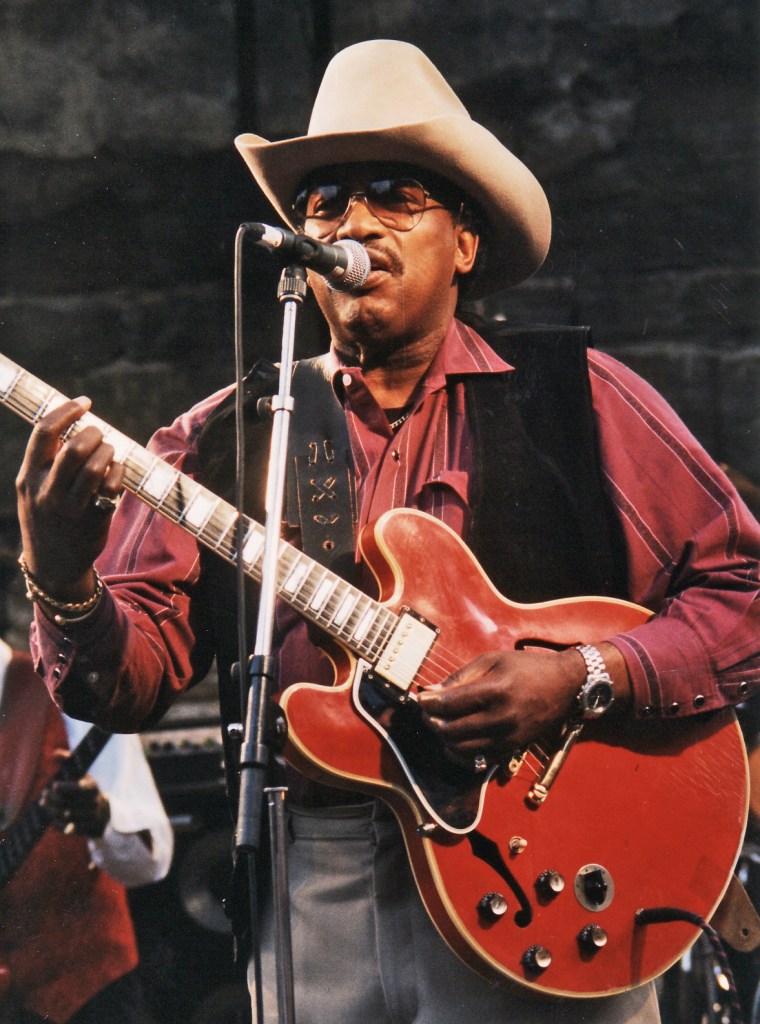

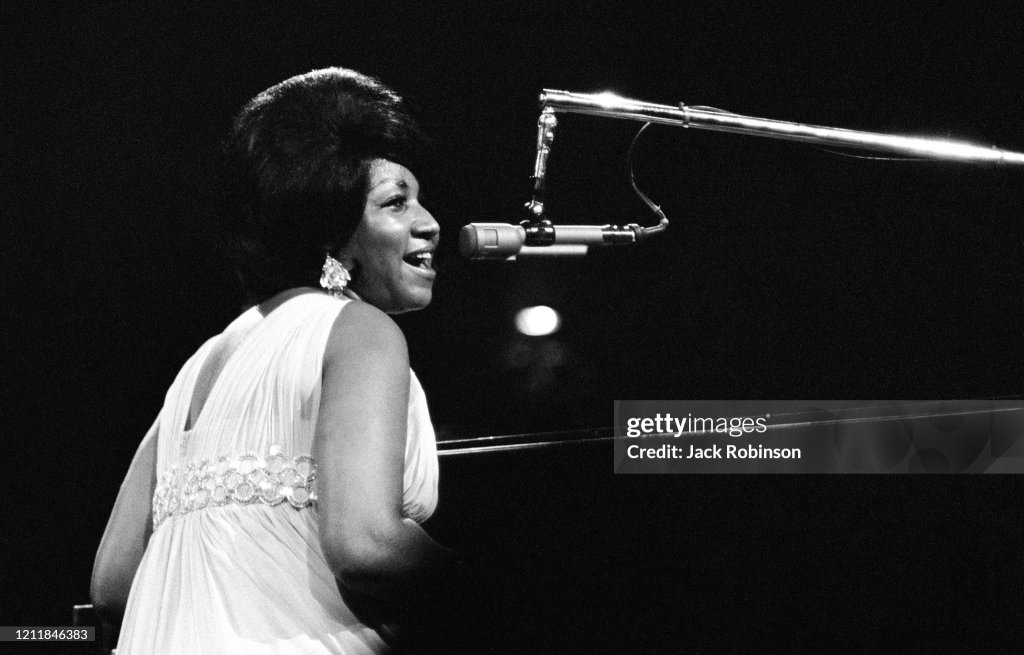

3. Adding Harmonic “Energy” to Your Music—regardless of the genre: One key thing that blues brings to modern music is the idea of “tension and release.” There is inherent dissonance in most blues harmony, working with that—especially the inherent tension between major and minor—adds a depth of expression to any music. There is also imperfection. Listen to the great blues singers and instrumentalists. Sliding into notes, adding that tinge of “almost minor” to a bend in a song based in a major key—or the opposite in a minor key. These are hallmarks of great blues artists, but also stock and trade for great rock artists, and soul, R&B, etc. Listen to how Robert Plant, Paul Rodgers, Aretha Franklin or Wilson Pickett do this instinctively—or even modern singers like Beyoncé and other soul and R&B artists like Bruno Mars. Also country artists like Chris Stapleton. Instrumentalists do this as well—especially the best blues harmonica players and slide guitarists like Duane Allman.

Here is a video of a discussion that YouTube and producer Rick Beato did with Rhett Shull and Dave Onorato. They were talking about how the loss of this blues influence in American music has had a negative impact. Find that here.

4. Imperfection: Listen carefully to the old recordings of rock and soul artists in particular. Aretha Franklin is a great example. She would slide into “almost” notes, and even would overdrive the pre-amps on the studio boards as she was a powerhouse in so many ways. This is the kind of thing that would be smoothed over with pitch correction, etc. if recorded today. But, here is where so much is lost. Slide guitar and harmonica players in particular were and are all about imperfection—often on purpose. This is the human emotional element that is often missing in today’s music. See the video link above for more specific lists of artists and the transition away from blues in rock music—and the impacts thereof. Blues brings a true, soul depth, human element. Getting this makes ALL the difference.

Bringing this all back should be the goal of all musicians today. I would argue that, “Blues energy” and harmony is the key to true emotional, soulful artistry in music. It brings a dimension that can’t really be replicated in any other way. There’s reason why entire music movements were formed around the power here. Early rock and roll and the hurricane of the “British Invasion” happened exactly because of everything mentioned here. The blues brings that emotional energy. Check the video mentioned above for more details on this perfection.

Get out, and learn and play the blues!

For more information on blues, blues artists and history and all things related to this music, visit Real Blues You can Use on Facebook, or go to our blog at: https://im-with-the-band.org/blog/

Mark Zanoni